Harmony with Water, Mountains, and Farmer-Artisans

Surrounded by an ocean side view, the winding Gonokawa River, and gentle rolling mountains, the village of Mizumi in Hamada City houses the only remaining four Sekishu washi manufacturing ateliers. Known to be the strongest among all Japanese paper, Sekishu Banshi (half sheets of Sekishu washi) is a UNESCO recognized Intangible Cultural Heritage made from just three ingredients: “kozo” (paper mulberry), “mitsumata” (oriental paper bush), or “gampi” (wikstroemia shrub), water, and an okra-like plant called tororo-aoi where its slime serves as a binding agent.

In the ancient times, this region, also known as the province of Iwami, had over 7,000 washi artisans-farmers who hand-crafted Sekishu washi during the winter off-season. They grew kozo along their terraced mountainside farmland to serve as a protective windbreak for their other crops. Today there still remains a farmer’s cooperative of 20+ farmers in Hamada who cultivate and harvest kozo every December.

Typically, the paper you might use is made from trees that grew for over 10 years and might last around 100 years. However, Sekishu washi is made from branches harvested after just one year and will produce paper that can last over 1,000 years. On Sekishu washi, things can almost live forever.

Intergenerational Community Threads

It is said that Sekishu washi and its methods were introduced by a famous poet, Kakinomoto no Hitomaro in 704-715 AD who taught local residents how to make paper. Sekishu washi was essential for Japanese society and life especially for merchants in Osaka and Tokyo. Today, you can even find mitsumata within Japanese currency.

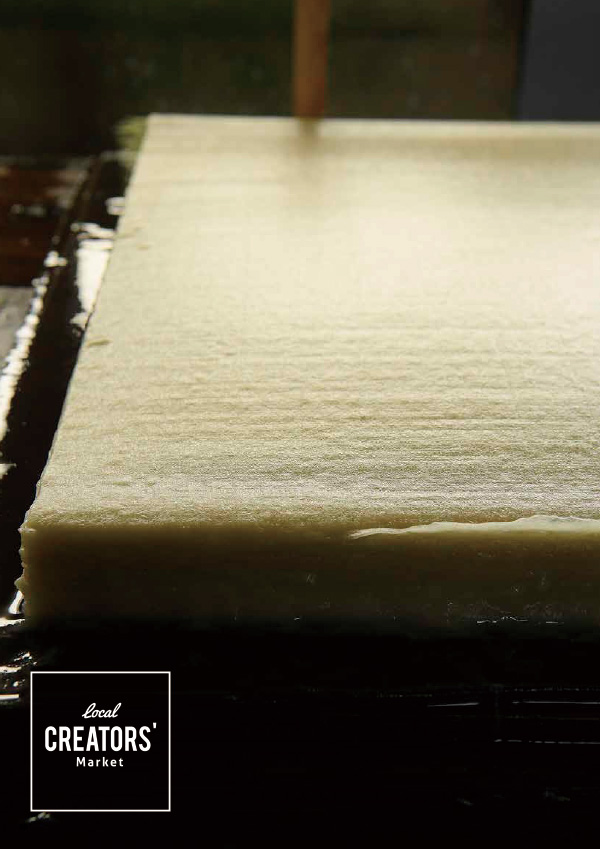

The entire Sekishu-washi production process is still done by hand from stripping the bark from the branches, scrapping the black bark, boiling the fibers, pounding, mixing, transferring, and sun drying the final product. What looks to be a seamless process of evenly distributing kozo/mitsumata/gampi fibers, water, and tororo aoi onto a bamboo screen actually requires at least 7 to 8 years of training before you can truly trust your own instinct and produce the kind of washi that meets your expectation and the expectation of each end user.

Every step of the process is meticulously cared for by many hands. Sekishu washi making is not possible without the support of Hamada’s entire community. Within each of the four artisan families, there is a commitment to passing this tradition onto the next generation. There are older women teaching other older women how to strip the bark as well as the washi masters raising younger apprentices to carry on this vital legacy. You can really feel that each sheet of this washi is made by the gifted hands of an entire community.

Sekishu Washi Speaks for Itself

In the same way a carpenter chooses their wood, there is an unspoken code of conduct between the Sekishu washi artisan and the next artisan that will choose to use Sekishu washi. Whether it be artists, writers, calligraphers, architects, monks, Japanese castle preservationists, or interior designers placing an order with Hamada’s washi makers, the quality of Sekishu washi speaks for itself.

In Hamada you can find Sekishu washi inside almost every resident’s home thanks to the community’s pride and joy for the traditional performance art of Iwami Kagura. Iwami Kagura is considered to be the oldest performance tradition with its origins in ancient Japanese mythology featuring deities and demons and today Hamada has over 60 performance groups putting on epic shows every Saturday for the whole community to enjoy! The fast tempo of the taiko and the dynamic melodies from the flute make Iwami Kagura highly entertaining. Each mask of the deities, demons, human characters, and the bodies of the serpent orochis are handcrafted made exclusively with Sekishu washi. These masks are often given as gifts to residents to serve as protection for their homes.