Brand Highlights

- • Plant-derived lacquer depletes no fossil materials and uses no harmful organic solvents

- • Exclusive trading rights in the late 1700s propelled the area into an innovative center of lacquerware production, as Kishu products became accessible throughout Japan

- • Our focus here is on certifi ed traditional artisans* who use only natural materials

Kishu lacquerware hails from the city of Kainan in northern Wakayama prefecture. Together with Aizu in Fukushima and Wajima in Ishikawa, Kainan is one of the three major centers of lacquerware production in Japan. Kishu lacquerware got its start in the late 1600s, when woodturners from present-day Shiga came to live in the Kuroe area of Kainan, drawn by its plentiful cypress wood. Lacquerers and painters of makie designs rendered with gold, silver, and other powders followed them. Shibuchi bowls, which used persimmon tannin in place of costly raw lacquer when forming the primer paste, helped to put Kishu products in the reach of commoners. In 1760 the artisans of Kuroe were granted exclusive trade rights from the domain. Fast-forward two centuries, and Kishu lacquerware was recognized by the national government as a traditional craft in 1978.

Synthetic polymers and coatings arrived in Kainan in the 1960s, opening the fl oodgates for cheaper, more easily produced wares. Today 90 percent of the lacquerers here use synthetic resin and polyurethane paints in place of natural lacquer. We introduce three certifi ed traditional artisans who, eschewing plastics, work to revive the old ways: Katsuhiko Hayashi and the father-daughter duo Toshifumi and Kumiko Tanioka.

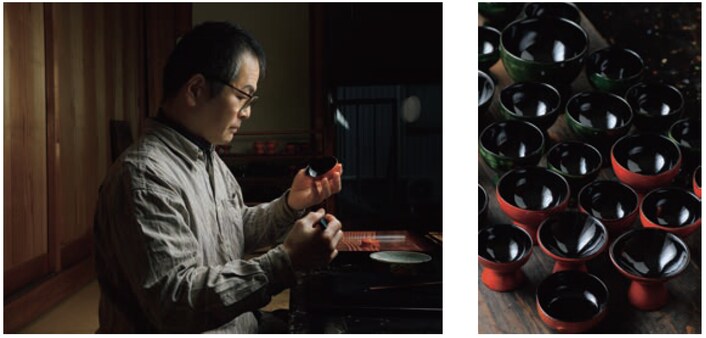

Katsuhiko Hayashi

Katsuhiko Hayashi is a makie artisan, like his Kishubased father and grandfather before him. Among his works are sake cups and fl asks fashioned out of hollowed-out gourds, as well as cups made of citrus peels. Just as is done when working with wood, he applies layer upon layer of lacquer to these all-natural materials to create a thoroughly unique piece. Hayashi’s interest in makie grew from around the age of 12, when he attended a lacquer-making workshop in which his father was involved. The event was fi lmed for television, and Hayashi was shown making his fi rst makie design. The scene might have been the idea of the TV producers, or it might have been his father trying to involve him in the family business. Either way, it worked: he was hooked.

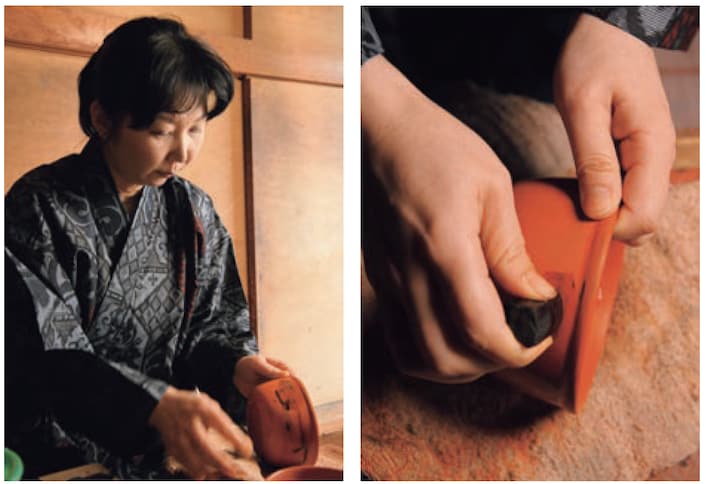

Kumiko Tanioka

Kumiko Tanioka is the fi rst woman in Kishu to earn the nationally certifi ed title of traditional artisan. She also represents the fi fth generation of Tanioka Lacquerware, founded in 1883 by a woodturner who came to Kishu for its abundant wood and eventually added lacquer work to his trade. The family workshop was on the second fl oor of her childhood home, so Tanioka grew up watching artisans come and go each day. All of her friends came from lacquerer families. She herself, however, was not interested in work that meant staying indoors most of the time.

Her view shifted in college, when a friend asked her about lacquerware. She realized she didn’t know enough about the history or techniques of her hometown tradition to explain them. After getting her master’s degree in economics she returned to Kainan, where she participated in a program set up to train successors in the lacquerware trade. She spent three months in the workshop of a makie expert and was fascinated. For the next ten years she apprenticed at various studios while holding down a teaching job at a cram school. She earned her certifi cate as a traditional artisan just as the base of the local industry was fl oundering. “I worked hard to become a traditional artisan. With so many veterans in the fi eld stepping down, I knew that something had to be done to preserve the craft—if only for the sake of those who had come before me,” she says. Tanioka considers herself an artisan, not an artist. She takes pride in fi lling orders for multiple quantities of the same item, each piece in the set as beautifully rendered as the next. Her work features on the tables of upscale restaurants in Tokyo’s Akasaka district, and most of her tsubo pots are purchased by foreigners.

Please refer to the Story Book for more article.