A symbol of elegance loved around the world since the early 1900s, Akoya pearls reveal a rainbow of hues beneath their translucent sheen. Whether a pearl is pink and perfectly spherical or white, black, blue, gold, or non-spherical baroque, its shimmering beauty is a gift of the sea.

Akoya pearls are sorted, processed and strung in Kobe before shipping, but they are grown in one of the top three pearl-farming regions in Japan—off the island of Tsushima in Nagasaki prefecture, Uwajima in Shikoku, or Ago Bay in Mie prefecture, where biodiverse coastlines are ideal for their cultivation.

Pearl culture begins with nucleation, or grafting—the operation that induces nacre secretion. After two to three years of growth, shellfish fry are ready for this most critical part of the culturing process. The nucleus, or what will become the core of the pearl, is a rounded shell fragment of an Eastern Asiatic freshwater clam, about six millimeters in diameter. With surgical precision, a technician uses a special tool to insert the nucleus into the oyster along with a mantle graft. Thus cultivated, the oyster is placed with others in a mesh bag and hung from a raft moored in the ocean, where they feed off plankton. Proper nutrition for the oysters affects the pearl harvest greatly, and oceanic conditions are monitored carefully.

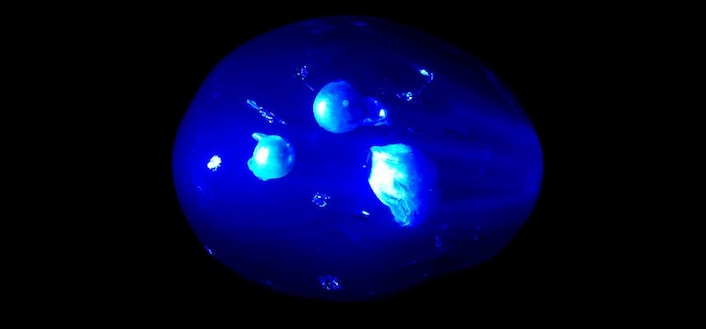

And what is happening inside the shell? First, the grafted mantle divides and wraps itself around the nucleus, creating a sac into which layer upon layer of crystalline nacre, formed mostly of calcium carbonate, is secreted by the oyster to enwrap the core. The inside of the shell—mother-of-pearl—is smooth, shiny, and multihued, just like the pearl. It’s provocative to consider that both the iridescent pearl and the shell that protects it are one and the same material.

One layer of nacre is 0.2 to 0.5 microns thick. (A single micron is one thousandth of a millimeter.) As the nucleus is six millimeters in diameter, it follows that anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500 layers of nacre are needed to form a 6.5-millimeter pearl. Such a complex crystalline matrix ensures that each one is unique, with its own depth of color and shine.

Of course, not every oyster will produce a pearl. Occasionally the core is spit out into the sea, and some oysters expire before their work is done. Barnacles and sea squirts can attach themselves to the shells, effectively starving the host. Akoya pearl farmers regularly check growing beds for these parasites and remove them by hand. The longer an oyster is left to grow, the larger its pearl becomes, but as an aging oyster nears death it secretes a substance that turns the pearl a dull matte white. The timing of the harvest is critical.

In the winter months nacre levels drop, but the thinner layer results in a delicate surface that gives a pearl its special radiance. In Tsushima, during the last week or so before the annual November harvest of oysters nucleated a year or two earlier, water temperatures are measured, samples from each lot are tested, and decisions are made on the best timing. With an early-morning start, as many as 50,000 of the shellfish are harvested each day.

Cultivated as they are in nutrient-rich waters, Akoya are beautiful even upon harvesting. But once they are processed and sorted in Kobe, home to some 200 pearl companies renowned for their polishing skills, these iridescent gems shine even more brightly, their inherent luster and beauty enhanced. Yellowing is removed to improve the natural shine, any blemishes are treated, and a thorough polish is given.

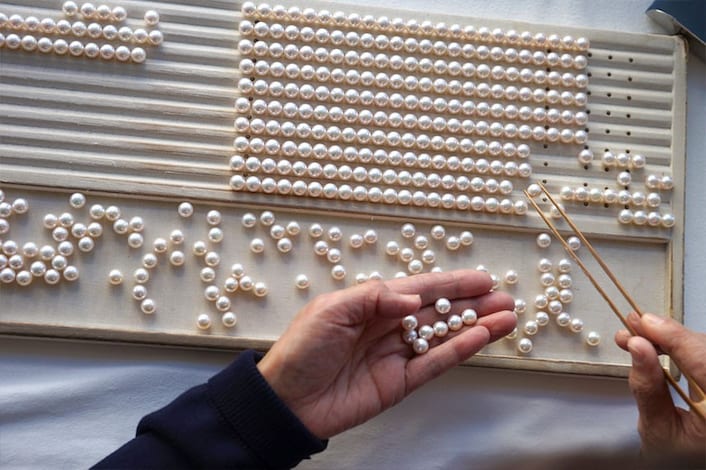

Finally, the pearls are ranked by eye. They are sorted in front of a north-facing window, where the low-angled natural light reveals any scratches or irregularities in shape and color. Artisans with a practiced eye recognize flaws as slight as one tenth of a millimeter. Years of experience turn each tiny orb into a thing of beauty. The pearls are batched, strung onto ropes, and sold in lots, then sent out into the world from Kobe Port—fulfillment of work that began in the ocean several years previously.

With so many factors affecting production, it seems a wonder that whole ropes of evenly sized pink pearls, considered the most precious, can even be possible. While the seasoned skills and exacting standards of growers play a huge role in creating these gems, the real benefactor is Mother Nature—and the delicate dance between sea and shell that ultimately cannot be controlled. Pink or blue, black or cream, each individual orb is a point of light in a tale that whispers quietly of the sea’s diverse riches.